- Other guides

- Beginner's guide

- JOSM - Detailed Editing

- Getting Started with JOSM

- The JOSM Editing Process

- Editing Field Data

- JOSM Editing Tools

- JOSM Plugins

- Opendata Plugin - data from a spreadsheet

- JOSM Building Tools & Utilsplugin2 plugins

- JOSM Presets

- JOSM - Creating Custom Presets

- JOSM Relations

- Aerial Imagery

- JOSM adding tms, wms or wmts imagery

- Correcting Imagery Offset

- JOSM Conflict Resolution

- Coordination

- Mapping with a SmartPhone, GPS or Paper

- OSM Data

- HOT Tips - Getting started for new mappers - iD editor

- Other Resources

|

|

Aerial Imagery

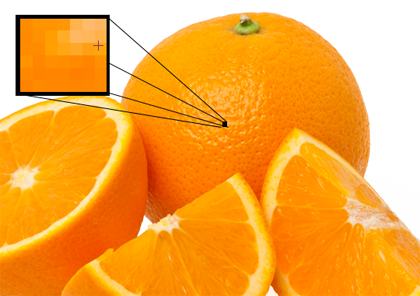

Tracing imagery is an easy and powerful way to contribute to OSM. Using imagery to draw points, lines and shapes on the ground is called digitizing. It can often be separated from the act of collecting attribute data on the ground, which is often called ground-truthing. Digtizing imagery can provide the skeleton of OSM maps, which makes ground-truthing easier for people in the field. In this chapter we’ll learn a little bit more about how aerial imagery works. About ImageryAerial imagery is the term that we use to describe photographs that are taken from the sky. These can be taken from airplanes, drones, helicopters, or even kites and balloons, but the most common source of imagery comes from satellites orbiting the Earth. In the chapter on GPS we learned about the dozens of satellites orbiting Earth which allow our GPS receivers to identify our latitude and longitude. In addition to these GPS satellites, there are also satellites which take photos of the earth. These photos are then manipulated so that they can be used in GIS (mapping) software. Bing Aerial Imagery is made up of satellite photos. ResolutionAll digital photographs are made up of pixels. If you zoom in very close on a photograph, you will notice the the image starts to get blurry, and eventually you’ll see that an image is made up of thousands of little squares that are each a different color. This is true whether the photograph is taken with a handheld camera, a mobile phone, or a satellite orbiting Earth.

Resolution refers to the number of pixels wide by the number of pixels high that an image is. More pixels means higher resolution, which means that you are able to see greater detail in the photograph. Resolution in handheld cameras is often measured in megapixels. The more megapixels your camera is able to record, the higher the resolution of your photos. Aerial imagery is the same, except that we usually talk about resolution differently. Measurement is important with aerial photographs - hence, a pixel represents a certain distance on the ground. We usually describe imagery as something like “two meter resolution imagery,” which means that one pixel is equivalent to two meters on the ground. One meter resolution imagery would have a higher resolution than this, and 50cm resolution would be higher still. This is generally the range of imagery that is provided by Bing, though it varies between locations, and in many places it is worse than two meters, at which point it becomes difficult to identify objects in the image.

The higher the resolution of an aerial image, the easier it is to use in making maps. GeoreferencingEach pixel of an aerial photograph has a size, and each pixel also has a location. As we mentioned above, this is because aerial photographs are georeferenced. Just like a GPS point has a latitude and longitude, so will the pixels in an aerial image. However, just as poor resolution can bring challenges to mapping, so can poorly georeferenced images. Let’s think for a moment about how georeferencing works, and why it is challenging to do. When somebody georeferences an image, they first identify a handful of pixels in the image that are known locations. If we have a square photograph, we might identify the coordinates of all four corners, and that way the whole image can be correctly placed. This all seems quite simple, but consider this: Earth is round; camera lenses are round; yet photographs are flat and 2-dimensional. This means that when a flat image is being mapped onto the round Earth, there is always going to be some stretching of the image and distortion. Imagine trying to flatten an orange-peel. It won’t end up rectangular. Because of this problem, all of the pixels in an aerial image might not be perfectly placed. Luckily, some really smart people have devised clever algorithms for solving this problem, and so the imagery that you see on Bing is pretty close to being accurate. In most places it won’t be noticeably wrong at all - and it’s certainly fine for making maps. The most common areas for imagery to be inaccurately located are in hilly, mountainous areas. In the Correcting Imagery Offset chapter we will see how to correct for this problem.

Was this chapter helpful?

Let us know and help us improve the guides!

|

Return to top of page

Return to top of page